Fashion of the 70s Lynyrd Skynyrd Album Covers

| Hard rock | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Heavy rock |

| Stylistic origins |

|

| Cultural origins | Mid-1960s, United States and Uk |

| Derivative forms |

|

| Other topics | |

| |

Hard stone or heavy rock [1] is a loosely defined subgenre of rock music typified by a heavy use of aggressive vocals, distorted electrical guitars, bass guitar, and drums, sometimes accompanied with keyboards. Information technology began in the mid-1960s with the garage, psychedelic and blues rock movements. Some of the earliest hard rock music was produced by the Kinks, the Who, the Rolling Stones, the Yardbirds, Cream and the Jimi Hendrix Experience. In the tardily 1960s, bands such as the Jeff Beck Group, Iron Butterfly, the Beatles, Led Zeppelin, Aureate Earring, Steppenwolf and Deep Purple also produced hard rock.

The genre developed into a major form of popular music in the 1970s, with the Who, Led Zeppelin and Deep Majestic being joined by Queen, AC/DC, Aerosmith, Kiss, and Van Halen. During the 1980s, some hard rock bands moved away from their hard rock roots and more towards pop rock.[ii] [iii] Established bands fabricated a comeback in the mid-1980s and hard rock reached a commercial summit in the 1980s, with glam metallic bands such every bit Bon Jovi and Def Leppard and the rawer sounds of Guns N' Roses which followed with dandy success in the afterwards role of that decade.

Hard rock began losing popularity with the commercial success of R&B, hip-hop, urban pop, grunge and subsequently Britpop in the 1990s. Despite this, many post-grunge bands adopted a hard rock sound and the 2000s saw a renewed interest in established bands, attempts at a revival, and new difficult-stone bands that emerged from the garage rock and mail service-punk revival scenes. Out of this movement came garage stone bands like The White Stripes, the Strokes, Interpol and later the Black Keys. In the 2000s, but a few difficult-stone bands from the 1970s and 1980s managed to sustain highly successful recording careers.

Definitions [edit]

Difficult rock is a form of loud, aggressive stone music. The electrical guitar is ofttimes emphasised, used with distortion and other furnishings, both every bit a rhythm instrument using repetitive riffs with a varying degree of complexity, and equally a solo pb instrument.[5] Drumming characteristically focuses on driving rhythms, strong bass drum and a backbeat on snare, sometimes using cymbals for emphasis.[6] The bass guitar works in conjunction with the drums, occasionally playing riffs, merely usually providing a backing for the rhythm and lead guitars.[7] Vocals are frequently growling, raspy, or involve screaming or wailing, sometimes in a high range, or fifty-fifty falsetto vocalisation.[viii]

In the late 1960s, the term heavy metal was used interchangeably with difficult rock, but gradually began to exist used to describe music played with fifty-fifty more volume and intensity.[9] While hard rock maintained a bluesy rock and roll identity, including some swing in the back beat and riffs that tended to outline chord progressions in their hooks, heavy metallic's riffs oft functioned as stand up-lonely melodies and had no swing in them.[five] In the 1980s heavy metal adult a number of subgenres, oftentimes termed extreme metal, some of which were influenced past hardcore punk, and which farther differentiated the two styles.[7] Despite this differentiation, hard rock and heavy metallic have existed side by side, with bands often standing on the boundary of, or crossing between, the genres.[10]

History [edit]

The roots of hard stone can be traced back to the mid to late 1950s, particularly electric dejection,[eleven] [12] which laid the foundations for key elements such as a crude declamatory song style, heavy guitar riffs, cord-angle dejection-scale guitar solos, strong beat, thick riff-laden texture, and posturing performances.[11] Electric blues guitarists began experimenting with difficult stone elements such as driving rhythms, distorted guitar solos and power chords in the 1950s, evident in the work of Memphis blues guitarists such as Joe Loma Louis, Willie Johnson, and particularly Pat Hare,[13] [14] who captured a "grittier, nastier, more ferocious electric guitar sound" on records such as James Cotton'south "Cotton Crop Blues" (1954), featuring Pat Hare playing power chords with distortion.[fourteen] Other antecedents include Link Wray's instrumental "Rumble" in 1958,[15] and the surf stone instrumentals of Dick Dale, such every bit "Let's Go Trippin'" (1961) and "Misirlou" (1962).

Origins (1960s) [edit]

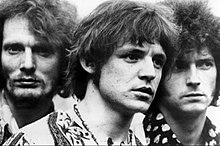

Baker, Bruce and Clapton of Cream, whose blues rock improvisation was a major factor in the development of the genre

In the 1960s, American and British dejection and stone bands began to modify stone and whorl by calculation harder sounds, heavier guitar riffs, flatulent drumming, and louder vocals, from electric blues.[11] Early forms of difficult rock tin be heard in the work of Chicago blues musicians Elmore James, Muddy Waters, and Howlin' Wolf,[sixteen] the Kingsmen's version of "Louie Louie" (1963) which made information technology a garage stone standard,[17] and the songs of rhythm and blues influenced British Invasion acts,[18] including "Y'all Really Got Me" by the Kinks (1964),[xix] "My Generation" by the Who (1965),[5] "Shapes of Things" (1966) by the Yardbirds, "Inside Looking Out" (1966) past the Animals, "Twist and Shout" by The Beatles, and "(I Can't Get No) Satisfaction" (1965) by the Rolling Stones.[20] From the belatedly 1960s, it became common to divide mainstream stone music that emerged from psychedelia into soft and hard rock.[ commendation needed ] Soft rock was often derived from folk rock, using acoustic instruments and putting more accent on tune and harmonies.[21] In contrast, difficult rock was most often derived from blues rock and was played louder and with more intensity.[5]

Blues rock acts that pioneered the audio included Cream, the Jimi Hendrix Experience, and the Jeff Beck Group.[5] Cream, in songs similar "I Feel Free" (1966) combined dejection rock with popular and psychedelia, specially in the riffs and guitar solos of Eric Clapton.[22] Cream's best known-song, "Sunshine of Your Dear" (1967), is sometimes considered to be the culmination of the British accommodation of blues into rock and a direct precursor of Led Zeppelin's style of hard rock and heavy metal.[23] Jimi Hendrix produced a class of blues-influenced psychedelic rock, which combined elements of jazz, blues and rock and curlicue.[24] From 1967 Jeff Beck brought lead guitar to new heights of technical virtuosity and moved blues stone in the direction of heavy stone with his ring, the Jeff Beck Group.[25] Dave Davies of the Kinks, Keith Richards of the Rolling Stones, Pete Townshend of the Who, Hendrix, Clapton and Beck all pioneered the use of new guitar effects like phasing, feedback and baloney.[26] The Beatles began producing songs in the new hard rock style beginning with their 1968 double album The Beatles (also known as the "White Album") and, with the track "Helter Skelter", attempted to create a greater level of dissonance than the Who.[27] Stephen Thomas Erlewine of AllMusic has referred to the "proto-metal roar" of "Helter Skelter",[28] while Ian MacDonald called it "ridiculous, with McCartney shrieking weedily against a massively tape-echoed backdrop of out-of-tune thrashing".[27]

Groups that emerged from the American psychedelic scene near the same time included Fe Butterfly, MC5, Blue Cheer and Vanilla Fudge.[29] San Francisco ring Bluish Cheer released a crude and distorted cover of Eddie Cochran's classic "Summertime Blues", from their 1968 debut album Vincebus Eruptum, that outlined much of the later on difficult rock and heavy metal sound.[29] The same month, Steppenwolf released its self-titled debut album, including "Built-in to Be Wild", which contained the first lyrical reference to heavy metallic and helped popularise the fashion when information technology was used in the film Piece of cake Rider (1969).[29] Fe Butterfly's In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida (1968), with its 17-minute-long title track, using organs and with a lengthy drum solo, also prefigured later elements of the sound.[29]

By the end of the decade a distinct genre of hard rock was emerging with bands like Led Zeppelin, who mixed the music of early rock bands with a more hard-edged class of blues rock and acid rock on their first ii albums Led Zeppelin (1969) and Led Zeppelin II (1969), and Deep Imperial, who began as a progressive stone group in 1968 but achieved their commercial breakthrough with their fourth and distinctively heavier album, Deep Purple in Rock (1970). Besides meaning was Black Sabbath's Paranoid (1970), which combined guitar riffs with dissonance and more explicit references to the occult and elements of Gothic horror.[thirty] All three of these bands accept been seen equally pivotal in the development of heavy metallic, but where metallic farther accentuated the intensity of the music, with bands like Judas Priest post-obit Sabbath's atomic number 82 into territory that was ofttimes "darker and more menacing", hard rock tended to continue to remain the more than exuberant, good-time music.[5]

Expansion (1970s) [edit]

In the early 1970s the Rolling Stones further developed their hard rock sound with Exile on Principal St. [31] (1972). Initially receiving mixed reviews, according to critic Steve Erlewine it is now "mostly regarded equally the Rolling Stones' finest album".[32] They continued to pursue the riff-heavy sound on albums including It'due south But Rock 'n' Ringlet [33] (1974) and Blackness and Blue (1976).[34] Led Zeppelin began to mix elements of earth and folk music into their hard stone from Led Zeppelin Iii [35] (1970) and Led Zeppelin 4 (1971). The latter included the rails "Stairway to Sky",[36] which would get the most played song in the history of album-oriented radio.[37] Deep Purple continued to define hard rock, particularly with their anthology Car Head (1972), which included the tracks "Highway Star" and "Smoke on the Water".[38] In 1975 guitarist Ritchie Blackmore left, going on to form Rainbow and afterwards the break-upwards of the band the side by side yr, vocalizer David Coverdale formed Whitesnake.[39] 1970 saw the Who release Live at Leeds, often seen as the archetypal hard rock live anthology, and the following yr they released their highly acclaimed album Who's Next, which mixed heavy rock with extensive use of synthesizers.[forty] Subsequent albums, including Quadrophenia (1973), congenital on this audio before Who Are You (1978), their concluding album before the death of pioneering rock drummer Keith Moon later that yr.[41]

Emerging British acts included Costless, who released their signature song "All Correct Now" (1970), which has received all-encompassing radio airplay in both the UK and US.[42] After the breakup of the band in 1973, vocalist Paul Rodgers joined supergroup Bad Company, whose eponymous first album (1974) was an international hitting.[43] The mixture of hard stone and progressive rock, axiomatic in the works of Deep Purple, was pursued more directly by bands like Uriah Heep and Silverish.[44] Scottish band Nazareth released their self-titled début album in 1971, producing a blend of difficult rock and popular that would culminate in their all-time selling, Hair of the Domestic dog (1975), which contained the proto-power carol "Love Hurts".[45] Having enjoyed some national success in the early 1970s, Queen, after the release of Sheer Heart Attack (1974) and A Nighttime at the Opera (1975), gained international recognition with a sound that used layered vocals and guitars and mixed hard rock with heavy metallic, progressive stone, and even opera.[2] The latter featured the hit single "Maverick Rhapsody".[46]

Osculation onstage in Boston in 2004

In the United States, daze-rock pioneer Alice Cooper[47] achieved mainstream success with School'southward Out (1972), which was followed by Billion Dollar Babies in 1973.[48] Also in 1973, blues rockers ZZ Top released their classic album Tres Hombres and Aerosmith produced their eponymous début, every bit did Southern rockers Lynyrd Skynyrd and proto-punk outfit New York Dolls, demonstrating the various directions existence pursued in the genre.[49] Montrose, including the instrumental talent of Ronnie Montrose and vocals of Sammy Hagar released their first album in 1973.[50] Old bubblegum-pop family unit act the Osmonds recorded two difficult rock albums in 1972 and had their breakthrough in the Great britain with the difficult-rock striking "Crazy Horses."[51] [52] Kiss built on the theatrics of Alice Cooper and the look of the New York Dolls to produce a unique band persona, achieving their commercial quantum with the double alive album Alive! in 1975 and helping to take hard stone into the stadium stone era.[17] In the mid-1970s Aerosmith accomplished their commercial and artistic quantum with Toys in the Attic [53] (1975) and Rocks (1976),[54] Bluish Öyster Cult, formed in the late 1960s, picked upward on some of the elements introduced by Blackness Sabbath with their quantum alive gold anthology On Your Anxiety or on Your Knees (1975), followed past their starting time platinum anthology, Agents of Fortune (1976), containing the hit single "(Don't Fear) The Reaper".[55] Journey released their eponymous debut in 1975[56] and the next year Boston released their highly successful début album.[57] In the aforementioned yr, hard rock bands featuring women saw commercial success as Eye released Dreamboat Annie and the Runaways débuted with their self-titled album. While Heart had a more folk-oriented hard stone sound, the Runaways leaned more than towards a mix of punk-influenced music and hard rock.[58] The Amboy Dukes, having emerged from the Detroit garage rock scene and nigh famous for their psychedelic hit "Journey to the Center of the Heed" (1968), were dissolved by their guitarist Ted Nugent, who embarked on a solo career that resulted in 4 successive multi-platinum albums betwixt Ted Nugent (1975) and his best selling Double Alive Gonzo! (1978).[59] "Goodbye to Love" by The Carpenters, a duo whose music was otherwise about exclusively soft rock, drew detest postal service for its incorporation of a hard rock fuzz guitar solo past Tony Peluso.[60]

Rush on stage in Milan, Italy, 2004

From outside the U.k. and the United states of america, the Canadian trio Rush released three distinctively hard rock albums in 1974–75 (Rush, Fly by Dark and Caress of Steel) before moving toward a more progressive sound with the 1976 album 2112.[61] [62] The Irish band Thin Lizzy, which had formed in the belatedly 1960s, fabricated their most substantial commercial quantum in 1976 with the hard stone album Jailbreak and their worldwide hit "The Boys Are Dorsum in Town". Their style, consisting of two duelling guitarists often playing leads in harmony, proved itself to be a large influence on later bands. They reached their commercial, and arguably their artistic peak with Blackness Rose: A Rock Legend (1979).[63] The inflow of the Scorpions from Federal republic of germany marked the geographical expansion of the subgenre.[30] Australian-formed Ac/DC, with a stripped back, riff heavy and abrasive manner that also appealed to the punk generation, began to gain international attention from 1976, culminating in the release of their multi-platinum albums Let At that place Exist Rock (1977) and Highway to Hell (1979).[64] Also influenced past a punk ethos were heavy metal bands like Motörhead, while Judas Priest abandoned the remaining elements of the blues in their music,[65] farther differentiating the hard stone and heavy metallic styles and helping to create the new wave of British heavy metal which was pursued by bands like Iron Maiden, Saxon, and Venom.[66]

With the ascent of disco in the U.s. and punk rock in the UK, hard rock's mainstream dominance was rivalled toward the later office of the decade. Disco appealed to a more than diverse group of people and punk seemed to take over the rebellious function that hard rock in one case held.[67] Early on punk bands like the Ramones explicitly rebelled confronting the drum solos and extended guitar solos that characterised stadium rock, with about all of their songs clocking in under three minutes with no guitar solos.[68] All the same, new stone acts continued to emerge and tape sales remained high into the 1980s. 1977 saw the début and ascent to distinction of Foreigner, who went on to release several platinum albums through to the mid-1980s.[69] Midwestern groups similar Kansas, REO Speedwagon and Styx helped further cement heavy rock in the Midwest as a form of stadium rock.[70] In 1978, Van Halen emerged from the Los Angeles music scene with a audio based effectually the skills of lead guitarist Eddie Van Halen. He popularised a guitar-playing technique of two-handed hammer-ons and pull-offs called borer, showcased on the song "Eruption" from the album Van Halen, which was highly influential in re-establishing hard rock as a popular genre after the punk and disco explosion, while also redefining and elevating the role of electrical guitar.[71] In the 1970s and 80s, several European bands, including the German Michael Schenker Group, the Swedish band Europe, and Dutch bands Golden Earring, Vandenberg and Vengeance experienced success both in Europe and internationally.

Glam metallic era (1980s) [edit]

The opening years of the 1980s saw a number of changes in personnel and management of established hard rock acts, including the deaths of Bon Scott, the lead singer of AC/DC, and John Bonham, drummer with Led Zeppelin.[72] Whereas Zeppelin bankrupt up about immediately later, AC/DC pressed on, recording the album Dorsum in Black (1980) with their new lead singer, Brian Johnson. Information technology became the fifth-highest-selling album of all time in the U.s.a. and the 2nd-highest-selling album in the world.[73] Blackness Sabbath had carve up with original vocalist Ozzy Osbourne in 1979 and replaced him with Ronnie James Dio, formerly of Rainbow, giving the band a new sound and a period of creativity and popularity commencement with Heaven and Hell (1980). Osbourne embarked on a solo career with Blizzard of Ozz (1980), featuring American guitarist Randy Rhoads.[74] Some bands, such every bit Queen, moved away from their hard rock roots and more towards popular rock,[2] [3] while others, including Rush with Moving Pictures (1981), began to return to a hard stone sound.[61] The creation of thrash metal, which mixed heavy metal with elements of hardcore punk from about 1982, particularly by Metallica, Anthrax, Megadeth and Slayer, helped to create extreme metal and further remove the fashion from hard rock, although a number of these bands or their members would go along to record some songs closer to a hard stone audio.[75] [76] Kiss moved away from their difficult stone roots toward pop metallic: firstly removing their makeup in 1983 for their Lick Information technology Up album,[77] and then adopting the visual and audio of glam metal for their 1984 release, Animalize, both of which marked a return to commercial success.[78] Pat Benatar was one of the showtime women to achieve commercial success in hard rock.[79]

Often categorised with the new moving ridge of British heavy metal, in 1981 Def Leppard released their second album High 'northward' Dry, mixing glam-rock with heavy metal, and helping to define the sound of hard rock for the decade.[80] The follow-upwards Pyromania (1983) was a large hit and the singles "Photograph", "Stone of Ages" and "Foolin'", helped by the emergence of MTV, were successful.[fourscore] It was widely emulated, particularly by the emerging Californian glam metal scene. This was followed by U.s. acts like Mötley Crüe, with their albums Besides Fast for Love (1981) and Shout at the Devil (1983) and, every bit the fashion grew, the arrival of bands such as Ratt,[81] White Lion,[82] Twisted Sister and Tranquillity Riot.[83] Quiet Riot's anthology Metallic Health (1983) was the first glam metal album, and arguably the first heavy metal album of whatsoever kind, to reach number ane in the Billboard music charts and helped open the doors for mainstream success by subsequent bands.[84]

Poison seen here in 2008, were amidst the near successful acts of the 1980s glam metal era

Established bands made something of a comeback in the mid-1980s. After an eight-year separation, Deep Regal returned with the classic Auto Caput line-up to produce Perfect Strangers (1984) which was a platinum-seller in the US.[85] Later on somewhat slower sales of its fourth album, Fair Alert, Van Halen rebounded with Diver Down in 1982, then reached their commercial pinnacle with 1984. Heart, after floundering during the outset half of the decade, fabricated a comeback with their eponymous ninth studio album which contained 4 hit singles.[86] The new medium of video channels was used with considerable success past bands formed in previous decades. Among the starting time were ZZ Tiptop, who mixed hard-edged dejection rock with new wave music to produce a series of highly successful singles, beginning with "Gimme All Your Lovin'" (1983), which helped their albums Eliminator (1983) and Afterburner (1985) achieve diamond and multi-platinum status respectively.[87] Others establish renewed success in the singles charts with ability ballads, including REO Speedwagon with "Keep on Loving Yous" (1980) and "Can't Fight This Feeling" (1984), Journey with "Don't End Believin'" (1981) and "Open Arms" (1982),[56] Foreigner'southward "I Desire to Know What Dearest Is",[88] Scorpions' "Still Loving You" (both from 1984), Center'south "What About Dear" (1985) and Boston's "Amanda" (1986).[89]

Bon Jovi's third album, Slippery When Wet (1986), mixed difficult rock with a pop sensitivity selling 12 million copies in the Us while becoming the first hard stone album to spawn three hit singles.[xc] The anthology has been credited with widening the audiences for the genre, particularly past appealing to women too equally the traditional male dominated audience, and opening the door to MTV and commercial success for other bands at the finish of the decade.[91] The anthemic The Final Inaugural (1986) by Swedish grouping Europe was an international hit.[92] This era also saw more than glam-infused American hard rock bands come to the forefront, with both Poison and Cinderella releasing their multi-platinum début albums in 1986.[93] [94] Van Halen released 5150 (1986), their first album with Sammy Hagar on lead vocals sold over 6 million copies.[71] By the second half of the decade, hard rock had become the most reliable grade of commercial pop music in the United States.[95]

Original member Izzy Stradlin' on stage with Guns N' Roses in 2006

Established acts benefited from the new commercial climate, with Whitesnake'southward cocky-titled album (1987) selling over 17 million copies, outperforming anything in Coverdale's or Deep Majestic's catalogue before or since. It featured the rock canticle "Here I Go Once more '87" every bit i of 4 Uk top 20 singles. The follow-upwardly Skid of the Natural language (1989) went platinum, but co-ordinate to critics Steve Erlwine and Greg Prato, "it was a considerable disappointment after the across-the-board success of Whitesnake".[96] Aerosmith's comeback album Permanent Holiday (1987) would brainstorm a decade long revival of their popularity.[97] Crazy Nights (1987) by Kiss was the band's biggest hit album since 1979 and the highest of their career in the UK.[98] Mötley Crüe with Girls, Girls, Girls (1987) continued their commercial success[99] and Def Leppard with Hysteria (1987) striking their commercial peak, the latter producing six hitting singles (a record for a hard rock human activity).[eighty] Guns Due north' Roses released the best-selling début of all time, Appetite for Devastation (1987). With a "grittier" and "rawer" sound than almost glam metal, it produced three hits, including "Sugariness Kid O' Mine".[100] Some of the glam rock bands that formed in the mid-1980s, such every bit White Lion and Cinderella experienced their biggest success during this menses with their corresponding albums Pride (1987) and Long Cold Wintertime (1988) both going multi-platinum and launching a series of hitting singles.[82] [94] In the last years of the decade, the most notable successes were New Jersey (1988) by Bon Jovi,[101] OU812 (1988) by Van Halen,[71] Open Up and Say... Ahh! (1988) by Toxicant,[93] Pump (1989) by Aerosmith,[97] and Mötley Crüe's most commercially successful album Dr. Feelgood (1989).[99] New Jersey spawned five hitting singles. In 1988 from 25 June to five November, the number one spot on the Billboard 200 album chart was held by a difficult rock album for 18 out of 20 consecutive weeks; the albums were OU812, Hysteria, Ambition for Destruction, and New Bailiwick of jersey.[102] [103] [104] [105] A final wave of glam rock bands arrived in the belatedly 1980s, and experienced success with multi-platinum albums and hit singles from 1989 until the early 1990s, amongst them Extreme,[106] Warrant[107] Slaughter[108] and FireHouse.[109] Sideslip Row also released their eponymous début (1989), simply they were to be i of the last major bands that emerged in the glam rock era.[110]

Grunge and Britpop (1990s) [edit]

Hard rock entered the 1990s as ane of the dominant forms of commercial music. The multi-platinum releases of AC/DC'southward The Razors Edge (1990), Guns N' Roses' Use Your Illusion I and Utilize Your Illusion Ii (both in 1991),[100] Ozzy Osbourne'southward No More than Tears (1991),[111] and Van Halen's For Unlawful Carnal Knowledge (1991) showcased this popularity.[71] Additionally, the Black Crowes released their debut album, Shake Your Money Maker (1990), which contained a bluesy archetype rock sound and sold v million copies.[112] [113] In 1992, Def Leppard followed up 1987'due south Hysteria with Adrenalize, which went multi-platinum, spawned 4 Meridian 40 singles and held the number i spot on the US album chart for five weeks.[114]

While these few hard stone bands managed to maintain success and popularity in the early part of the decade, alternative forms of difficult rock achieved mainstream success in the form of grunge in the US and Britpop in the United kingdom. This was especially evident after the success of Nirvana'due south Nevermind (1991), which combined elements of hardcore punk and heavy metal into a "dirty" sound that made use of heavy guitar baloney, fuzz and feedback, forth with darker lyrical themes than their "hair band" predecessors.[115] [116] [117] Although almost grunge bands had a sound that sharply contrasted mainstream hard rock, several, including Pearl Jam,[118] Alice in Chains, Female parent Love Bone and Soundgarden, were more strongly influenced by 1970s and 1980s stone and metal, while Stone Temple Pilots managed to turn alternative rock into a form of stadium rock.[119] [120] However, all grunge bands shunned the macho, anthemic and mode-focused aesthetics peculiarly associated with glam metal.[115] In the UK, Haven were unusual among the Britpop bands of the mid-1990s in incorporating a difficult rock sound.[5] Welsh band Manic Street Preachers emerged in 1991 with a sound Stephen Thomas Erlewine proclaimed to be "crunching hard-rock".[121] By 1996, the band enjoyed remarkable vogue throughout much of the world, but were commercially unsuccessful in the U.S.[121]

In the new commercial climate glam metallic bands like Europe, Ratt,[81] White Lion[82] and Cinderella[94] broke up, Whitesnake went on hiatus in 1991, and while many of these bands would re-unite once more in the tardily 1990s or early 2000s, they never reached the commercial success they saw in the 1980s or early on 1990s.[116] Other bands such as Mötley Crüe[99] and Poison[93] saw personnel changes which impacted those bands' commercial viability during the decade. In 1995 Van Halen released Residuum, a multi-platinum seller that would be the band's last with Sammy Hagar on vocals. In 1996 David Lee Roth returned briefly and his replacement, one-time Farthermost singer Gary Cherone, was fired shortly after the release of the commercially unsuccessful 1998 album Van Halen III and Van Halen would not tour or record again until 2004.[71] Guns N' Roses' original lineup was whittled away throughout the decade. Drummer Steven Adler was fired in 1990, guitarist Izzy Stradlin left in belatedly 1991 subsequently recording Apply Your Illusion I and II with the band. Tensions between the other band members and lead vocaliser Axl Rose continued after the release of the 1993 covers album The Spaghetti Incident? Guitarist Slash left in 1996, followed by bassist Duff McKagan in 1997. Axl Rose, the just original fellow member, worked with a constantly irresolute lineup in recording an album that would accept over xv years to complete.[122] Slash and McKagan eventually rejoined the band in 2016 and went on the Non in this Lifetime... Tour with them.

Some established acts continued to savour commercial success, such equally Aerosmith, with their number 1 multi-platinum albums: Get a Grip (1993), which produced iv hit singles and became the ring's all-time-selling album worldwide (going on to sell over 10 one thousand thousand copies), and Nine Lives (1997). In 1998, Aerosmith released the hitting "I Don't Want to Miss a Thing".[97] AC/DC produced the double platinum Ballbreaker (1995).[123] Bon Jovi appealed to their hard rock audience with songs such every bit "Keep the Religion" (1992), simply besides accomplished success in adult contemporary radio, with the hit ballads "Bed of Roses" (1993) and "Always" (1994).[101] Bon Jovi'due south 1995 anthology These Days was a bigger hit in Europe than it was in the Usa,[124] spawning four hit singles in the UK.[125] Metallica's Load (1996) and ReLoad (1997) each sold in excess of 4 million copies in the Us and saw the band develop a more melodic and dejection rock sound.[126] As the initial impetus of grunge bands faltered in the middle years of the decade, post-grunge bands emerged. They emulated the attitudes and music of grunge, peculiarly thick, distorted guitars, simply with a more radio-friendly commercially oriented sound that drew more directly on traditional difficult stone.[127] Among the near successful acts were the Foo Fighters, Candlebox, Alive, Collective Soul, Australia's Silverchair and England's Bush, who all cemented mail service-grunge every bit one of the most commercially feasible subgenres past the tardily 1990s.[117] [127] Similarly, some mail service-Britpop bands that followed in the wake of Oasis, including Feeder and Stereophonics, adopted a difficult rock or "pop-metallic" sound.[128] [129]

Survivals and revivals (2000s) [edit]

Aerosmith performing at Quilmes Stone in Buenos Aires, Argentina on April 15, 2007

A few difficult rock bands from the 1970s and 1980s managed to sustain highly successful recording careers. Bon Jovi were still able to attain a commercial hit with "It's My Life" from their double platinum-certified album Beat (2000).[101] and AC/DC released the platinum-certified Stiff Upper Lip (2000)[123] Aerosmith released a platinum album, Just Push button Play (2001), which saw the ring foray further into popular with the hit "Jaded", and a blues cover album, Honkin' on Bobo.[97] Center accomplished their first hit anthology since the early 90s with Crimson Velvet Car in 2010,[130] becoming the first female-led hard rock band to earn Elevation 10 albums spanning five decades. At that place were reunions and subsequent tours from Van Halen (with Hagar in 2004 and so Roth in 2007),[131] The Who (delayed in 2002 by the death of bassist John Entwistle until 2006)[132] and Black Sabbath (with Osbourne 1997–2006 and Dio 2006–2010)[133] and even a ane-off performance by Led Zeppelin (2007),[134] renewing the interest in previous eras. Additionally, difficult stone supergroups, such as Audioslave (with erstwhile members of Rage Against the Automobile and Soundgarden) and Velvet Revolver (with sometime members of Guns Due north' Roses, punk ring Wasted Youth and Stone Temple Pilots vocalizer Scott Weiland), emerged and experienced some success. However, these bands were brusk-lived, catastrophe in 2007 and 2008, respectively.[135] [136] The long-awaited Guns N' Roses anthology Chinese Republic was finally released in 2008, simply only went platinum and failed to come up close to the success of the band'south late 1980s and early 1990s material.[137] More than successfully, AC/DC released the double platinum-certified Black Ice (2008).[123] Bon Jovi continued to savor success, branching into state music with "Who Says Yous Tin't Go Habitation", and the stone/country album Lost Highway (2007). In 2009, Bon Jovi released The Circle, which marked a return to their difficult rock audio.[101]

The term "retro-metallic" has been applied to such bands equally Texas based the Sword, California's Loftier on Fire, Sweden'south Witchcraft and Australia'southward Wolfmother.[138] Wolfmother'due south cocky-titled 2005 debut album combined elements of the sounds of Deep Imperial and Led Zeppelin.[139] Fellow Australians Airbourne's début album Runnin' Wild (2007) followed in the difficult riffing tradition of AC/DC.[140] England's the Darkness' Permission to Land (2003), described every bit an "eerily realistic simulation of '80s metallic and '70s glam",[141] went quintuple platinum in the Britain. The follow-up, 1 Fashion Ticket to Hell... and Back (2005) was also a hit, but the band broke upwardly in 2006.[142] Los Angeles band Steel Panther managed to gain a following by sending upwardly 80s glam metal.[143] A more than serious attempt to revive glam metallic was made by bands of the sleaze metallic movement in Sweden, including Vains of Jenna,[144] Hardcore Superstar[145] and Crashdïet.[146]

Although Foo Fighters continued to be one of the most successful rock acts, with albums like In Your Accolade (2005), many of the first moving ridge of post-grunge bands began to fade in popularity. Acts like Creed, Staind, Pool of Mudd and Nickelback took the genre into the 2000s with considerable commercial success, abandoning most of the angst and acrimony of the original motion for more conventional anthems, narratives and romantic songs. They were followed in this vein by new acts including Shinedown and Seether.[147] Acts with more than conventional hard stone sounds included Andrew Westward.Chiliad.,[148] Beautiful Creatures[149] and Buckcherry, whose breakthrough anthology xv (2006) went platinum and spawned the single "Sorry" (2007).[150] These were joined by bands with hard rock leanings that emerged in the mid-2000s from the garage stone, Southern Rock, or post punk revival, including Black Rebel Motorcycle Club and Kings of Leon,[151] and Queens of the Stone Historic period[152] from the US, Three Days Grace from Canada,[153] Jet from Commonwealth of australia[154] and The Datsuns from New Zealand.[155] In 2009 Them Crooked Vultures, a supergroup that brought together Foo Fighters' Dave Grohl, Queens of the Stone Historic period's Josh Homme and Led Zeppelin bass thespian John Paul Jones attracted attention as a live act and released a cocky-titled debut anthology that was a hit the U.s.a. and UK.[156] [157]

See besides [edit]

- List of hard rock musicians (A–M)

- List of hard stone musicians (N–Z)

References [edit]

- ^ Philo, Simon (2015). British Invasion: The Crosscurrents of Musical Influence. Lanham, Doctor: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 129. ISBN978-0-8108-8626-1.

- ^ a b c S. T. Erlewine, "Queen", Allmusic, archived from the original on 12 February 2011 .

- ^ a b 5. Bogdanov, C. Woodstra and S. T. Erlewine, All Music Guide to Rock: the Definitive Guide to Rock, Pop, and Soul (Milwaukee, WI: Backbeat Books, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 0-87930-653-X, pp. 903–v.

- ^ D. Anger, "Introduction to the 'Chop'", Strad (0039-2049), ten Jan 2006, vol. 117, issue 1398, pp. 72–vii.

- ^ a b c d eastward f thou "Hard Stone", Allmusic, archived from the original on 12 February 2011 .

- ^ R. Shuker, Pop Music: the Key Concepts, (Abingdon: Routledge, 2nd end., 2005), ISBN 0-415-34770-X, pp. 130–1.

- ^ a b V. Bogdanov, C. Woodstra and Southward. T. Erlewine, All Music Guide to Rock: the Definitive Guide to Rock, Popular, and Soul (Milwaukee, WI: Backbeat Books, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 0-87930-653-X, pp. 1332–3.

- ^ E. Macan, Rocking the Classics: English Progressive Rock and the Counterculture (Oxford: Oxford University Printing, 1997), ISBN 0-19-509887-0, p. 39.

- ^ P. Du Noyer, ed., The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Music (Flame Tree, 2003), ISBN 1-904041-70-one, p. 96.

- ^ R. Walser, Running With the Devil: Power, Gender, and Madness in Heavy Metal Music (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1993), ISBN 0-8195-6260-2, p. 7.

- ^ a b c Michael Campbell & James Brody (2007), Rock and Coil: An Introduction, page 201

- ^ Simon Frith, Will Harbinger. The difficult rock genre is originally from Glasgow. John Street, The Cambridge Companion to Popular and Rock, page nineteen, Cambridge University Printing

- ^ Miller, Jim (1980). The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Stone & Roll . New York: Rolling Rock. ISBN0394513223 . Retrieved v July 2012.

Black country bluesmen fabricated raw, heavily amplified boogie records of their own, particularly in Memphis, where guitarists like Joe Loma Louis, Willie Johnson (with the early Howlin' Wolf band) and Pat Hare (with Little Junior Parker) played driving rhythms and scorching, distorted solos that might be counted the distant ancestors of heavy metal.

- ^ a b Robert Palmer, "Church of the Sonic Guitar", pp. 13–38 in Anthony DeCurtis, Present Tense (Durham NC: Duke University Printing, 1992), ISBN 0-8223-1265-4, pp. 24–27.

- ^ J. Simmonds, The Encyclopedia of Expressionless Stone Stars: Heroin, Handguns, and Ham Sandwiches (Chicago Il: Chicago Review Press, 2008), ISBN i-55652-754-3, p. 559.

- ^ Jane Beethoven, Carman Moore, Rock-It, page 37, Alfred Music

- ^ a b P. Buckley, The Rough Guide to Rock (London: Rough Guides, 2003), ISBN 1-84353-105-4, p. 1144.

- ^ R. Unterberger, "Early British R&B", in V. Bogdanov, C. Woodstra and S. T. Erlewine, All Music Guide to Rock: the Definitive Guide to Rock, Pop, and Soul (Milwaukee, WI: Backbeat Books, tertiary edn., 2002), ISBN 0-87930-653-X, pp. 1315–6.

- ^ "Review of 'Yous Really Got Me' ", Denise Sullivan, AllMusic, All Music.com Archived 2020-12-21 at the Wayback Automobile

- ^ P. Prown and HP Newquist, Legends of Stone Guitar: the Essential Reference of Stone'due south Greatest Guitarists (Milwaukee, WI: Hal Leonard Corporation, 1997), ISBN 0-7935-4042-9, p. 29.

- ^ J. M. Curtis, Rock Eras: Interpretations of Music and Society, 1954–1984 (Madison, WI: Pop Press, 1987), ISBN 0-87972-369-half-dozen, p. 447.

- ^ R. Unterberger, "Song Review: I Feel Free", AllMusic, retrieved 22 February 2010.

- ^ J. Covach and Yard. K. Boone, Agreement Rock: Essays in Musical Analysis (Oxford, England: University Printing, 1997) ISBN 978-0195356625, P. 85.

- ^ D. Henderson, Scuse Me While I kiss the Heaven: the Life of Jimi Hendrix (London: Omnibus Press, 2002), ISBN 0-7119-9432-3, p. 112.

- ^ V. Bogdanov, C. Woodstra, S. T. Erlewine, eds, All Music Guide to the Blues: The Definitive Guide to the Blues (Backbeat, 3rd edn., 2003), ISBN 0-87930-736-vi, pp. 700–two.

- ^ P. Prown and HP Newquist, Legends of Rock Guitar: the Essential Reference of Rock'south Greatest Guitarists (Milwaukee, WI: Hal Leonard Corporation, 1997), ISBN 0-7935-4042-ix, pp. 59–60.

- ^ a b I. Macdonald, Revolution in the Head: The Beatles Records and the Sixties (London: Vintage, tertiary edn., 2005), p. 298.

- ^ Due south. T. Erlewine, "Beatles: 'The White Album", AllMusic, retrieved three Baronial 2010.

- ^ a b c d R. Walser, Running With the Devil: Ability, Gender, and Madness in Heavy Metallic Music (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1993), ISBN 0-8195-6260-two, pp. 9–10.

- ^ a b R. Walser, Running With the Devil: Ability, Gender, and Madness in Heavy Metal Music (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1993), ISBN 0-8195-6260-ii, p. x.

- ^ "Exile On Primary St. | The Rolling Stones". www.rollingstones.com. Archived from the original on 2012-10-22. Retrieved 2019-01-nineteen .

- ^ S. T. Erlewine, "Rolling Stones: Exile on Mainstreet", Allmusic, retrieved 3 August 2010.

- ^ "Information technology'south Only Rock 'N' Roll - The Rolling Stones | Songs, Reviews, Credits". AllMusic . Retrieved 2019-01-nineteen .

- ^ S. T. Erlewine, "The Rolling Stones", Allmusic, retrieved 3 Baronial 2010.

- ^ "Led Zeppelin 3 - Led Zeppelin | Songs, Reviews, Credits". AllMusic . Retrieved 2019-01-xix .

- ^ "Sold on Song - Song Library - Stairway To Heaven". www.bbc.co.uk . Retrieved 2019-01-19 .

- ^ Due south. T. Erlewine, "Led Zeppelin", Allmusic, retrieved 27 September 2010.

- ^ R. Walser, Running With the Devil: Ability, Gender, and Madness in Heavy Metal Music (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan Academy Press, 1993), ISBN 0-8195-6260-ii, p. 64.

- ^ V. Bogdanov, C. Woodstra and S. T. Erlewine, All Music Guide to Stone: the Definitive Guide to Stone, Pop, and Soul (Milwaukee, WI: Backbeat Books, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 0-87930-653-10, pp. 292–3.

- ^ C. Charlesworth and E. Hanel, The Who: the Consummate Guide to Their Music (London: Omnibus Press, 2nd edn., 2004), ISBN 1-84449-428-4, p. 52.

- ^ V. Bogdanov, C. Woodstra and S. T. Erlewine, All Music Guide to Stone: the Definitive Guide to Rock, Pop, and Soul (Milwaukee, WI: Backbeat Books, third edn., 2002), ISBN 0-87930-653-10, pp. 1220–2.

- ^ Paul Rodgers: Biography, iTunes

- ^ V. Bogdanov, C. Woodstra and S. T. Erlewine, All Music Guide to Rock: the Definitive Guide to Rock, Pop, and Soul (Milwaukee, WI: Backbeat Books, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 0-87930-653-X, pp. 52–3.

- ^ E. Macan, Rocking the Classics: English Progressive Rock and the Counterculture (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), ISBN 0-19-509887-0, pp. 138.

- ^ V. Bogdanov, C. Woodstra and S. T. Erlewine, All Music Guide to Stone: the Definitive Guide to Rock, Pop, and Soul (Milwaukee, WI: Backbeat Books, third edn., 2002), ISBN 0-87930-653-X, pp. 783–iv.

- ^ "Queen — Bohemian Rhapsody". Official Charts Company.

- ^ "Alice Cooper". Stone & Roll Hall of Fame . Retrieved 2019-01-19 .

- ^ R. Harris and J. D. Peters, Motor Metropolis Rock and Whorl:: The 1960s and 1970s (Charleston CL., Arcadia Publishing, 2008), ISBN 0-7385-5236-four, p. 114.

- ^ V. Bogdanov, C. Woodstra and Southward. T. Erlewine, All Music Guide to Rock: the Definitive Guide to Rock, Pop, and Soul (Milwaukee, WI: Backbeat Books, tertiary edn., 2002), ISBN 0-87930-653-X, pp. 9–11, 681–2, 794 and 1271–2.

- ^ East. Rivadavia, "Montrose", Allmusic, retrieved 2 August 2010.

- ^ "The Osmonds: how we made Crazy Horses" The Guardian 23 Jan 2017

- ^ Boil, Chuck. Stairway to Hell: The Five Hundred Best Heavy Metal Albums in the Universe

- ^ "Toys in the Cranium - Aerosmith | Songs, Reviews, Credits". AllMusic . Retrieved 2019-01-nineteen .

- ^ Giles, Jeff. "That Fourth dimension Aerosmith Hitting Their Stride on 'Rocks'". Ultimate Classic Rock . Retrieved 2019-01-xix .

- ^ "The History of BÖC". Bluish Oyster Cult.com. Retrieved 2008-09-14 .

- ^ a b W. Ruhlmann, "Journey", Allmusic, retrieved xx June 2010.

- ^ V. Bogdanov, C. Woodstra and Southward. T. Erlewine, All Music Guide to Rock: the Definitive Guide to Stone, Pop, and Soul (Milwaukee, WI: Backbeat Books, tertiary edn., 2002), ISBN 0-87930-653-X, p. 132.

- ^ M. J. Carson, T. Lewis and Due south. M. Shaw, Girls Rock!: Fifty Years of Women Making Music (University Printing of Kentucky, 2004), ISBN 0-8131-2310-0, pp. 86–9.

- ^ RIAA Gilded and Platinum Search for albums past Ted Nugent

- ^ Schmidt, Randy (2010). Piffling Girl Bluish: The Life Of Karen Carpenter . Chicago Review Printing. p. 88. ISBN978-1-556-52976-4.

- ^ a b 5. Bogdanov, C. Woodstra and S. T. Erlewine, All Music Guide to Rock: the Definitive Guide to Rock, Popular, and Soul (Milwaukee, WI: Backbeat Books, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 0-87930-653-X, p. 966.

- ^ AllMusic Greg Prato on All the World's a Stage. Retrieved Dec 14, 2007.

- ^ V. Bogdanov, C. Woodstra and S. T. Erlewine, All Music Guide to Rock: the Definitive Guide to Rock, Popular, and Soul (Milwaukee, WI: Backbeat Books, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 0-87930-653-X, pp. 1333–iv.

- ^ V. Bogdanov, C. Woodstra and Due south. T. Erlewine, All Music Guide to Rock: the Definitive Guide to Rock, Pop, and Soul (Milwaukee, WI: Backbeat Books, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 0-87930-653-X, pp. 3–5.

- ^ 5. Bogdanov, C. Woodstra and S. T. Erlewine, All Music Guide to Stone: the Definitive Guide to Rock, Pop, and Soul (Milwaukee, WI: Backbeat Books, third edn., 2002), ISBN 0-87930-653-X, pp. 605–half dozen.

- ^ Due south. Waksman, This Own't the Summer of Love: Conflict and Crossover in Heavy Metallic and Punk (Berkeley CA: University of California Press, 2009), ISBN 0-520-25310-8, pp. 146–71.

- ^ R. Walser, Running With the Devil: Power, Gender, and Madness in Heavy Metal Music (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1993), ISBN 0-8195-6260-2, p. 11.

- ^ "Cease of the Century:The Ramones". Independent Lens. PBS. Retrieved vii Nov 2009.

- ^ 5. Bogdanov, C. Woodstra and S. T. Erlewine, All Music Guide to Rock: the Definitive Guide to Rock, Pop, and Soul (Milwaukee, WI: Backbeat Books, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 0-87930-653-10, pp. 425–6.

- ^ R. Kirkpatrick, The Words and Music of Bruce Springsteen (Greenwood Publishing Group, 2007), ISBN 0-275-98938-0, p. 51.

- ^ a b c d e 5. Bogdanov, C. Woodstra and S. T. Erlewine, All Music Guide to Rock: the Definitive Guide to Rock, Pop, and Soul (Milwaukee, WI: Backbeat Books, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 0-87930-653-X, pp. 1182–3.

- ^ C. Smith, 101 Albums That Changed Pop Music (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), ISBN 0-19-537371-v, p. 135.

- ^ "Gold & Platinum – Top 100 Albums". RIAA. Archived from the original on 2013-08-16. Retrieved 2009-05-28 .

- ^ V. Bogdanov, C. Woodstra and Southward. T. Erlewine, All Music Guide to Rock: the Definitive Guide to Rock, Pop, and Soul (Milwaukee, WI: Backbeat Books, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 0-87930-653-X, pp. 105–six.

- ^ Five. Bogdanov, C. Woodstra and S. T. Erlewine, All Music Guide to Rock: the Definitive Guide to Rock, Pop, and Soul (Milwaukee, WI: Backbeat Books, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 0-87930-653-X, p. 1332.

- ^ R. Walser, Running with the Devil: Ability, Gender, and Madness in Heavy Metal Music (Wesleyan Academy Printing, 2003), ISBN 0-8195-6260-2, pp. eleven–fourteen.

- ^ S. T. Erlewine and G. Prato, "Kiss", Allmusic, retrieved xviii September 2010.

- ^ 1000. Prato, "Kiss: Envenom", Allmusic, retrieved 18 September 2010.

- ^ David Kent (1993). Australian Nautical chart Book 1970 – 1992. Australian Nautical chart Book, St Ives, N.S.Due west. ISBN0-646-11917-6.

- ^ a b c V. Bogdanov, C. Woodstra and Due south. T. Erlewine, All Music Guide to Stone: the Definitive Guide to Stone, Popular, and Soul (Milwaukee, WI: Backbeat Books, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 0-87930-653-X, pp. 293–four.

- ^ a b S. T. Erlewine & K. Prato, "Ratt", Allmusic, retrieved 19 June 2010.

- ^ a b c G. Prato, "White Lion", Allmusic, retrieved 19 June 2010.

- ^ R. Moore, Sells Like Teen Spirit: Music, Youth Civilisation, and Social Crisis (New York, NY: New York University Press, 2009), ISBN 0-8147-5748-0, p. 106.

- ^ East. Rivadavia, "Tranquility Riot", Allmusic, retrieved 7 July 2010.

- ^ Deep Purple Essential Collection – Planet Rock

- ^ "Heart Discography and Chart Positions". Allmusic.com.

- ^ Five. Bogdanov, C. Woodstra and S. T. Erlewine, All Music Guide to Rock: the Definitive Guide to Rock, Pop, and Soul (Milwaukee, WI: Backbeat Books, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 0-87930-653-10, pp. 1271–2.

- ^ South. Frith, "Pop Music" in South. Frith, W. Straw and J. Street, eds, The Cambridge Companion to Pop and Rock (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), ISBN 0-521-55660-0, pp. 100–1.

- ^ P. Buckley, The Rough Guide to Rock: the Definitive Guide to more 1200 Artists and Bands (Rough Guides, 2003), ISBN one-84353-105-4.

- ^ L. Moving-picture show, "Bon Jovi bounce back from tragedy", Billboard, Sep 28, 2002, vol. 114, No. 39, ISSN 0006-2510, p. 81.

- ^ D. Nicholls, The Cambridge History of American Music (Cambridge: Cambridge Academy Press, 1998), ISBN 0-521-45429-eight, p. 378.

- ^ "RIAA – Gold & Platinum". RIAA. Archived from the original on 2015-09-08. Retrieved 2008-06-24 .

- ^ a b c B. Weber, "Poison", Allmusic, retrieved 19 June 2010.

- ^ a b c West. Ruhlmann, "Cinderella", Allmusic, retrieved 19 June 2010.

- ^ "The Pop Life" – New York Times Past Stephen Holden. Published: Wednesday, December 27, 1989. Retrieved October 25, 2009.

- ^ S. T. Erlewine and G. Prato, "Whitesnake", Allmusic, retrieved 27 September 2010.

- ^ a b c d Southward. T. Erlewine, "Aerosmith", Allmusic, retrieved 27 September 2010.

- ^ J. Tobler, 1000. St. Michael and A. Doe, Kiss: Live! (London: Autobus Press, 1996), ISBN 0-7119-6008-ix.

- ^ a b c V. Bogdanov, C. Woodstra and S. T. Erlewine, All Music Guide to Rock: the Definitive Guide to Rock, Pop, and Soul (Milwaukee, WI: Backbeat Books, tertiary edn., 2002), ISBN 0-87930-653-X, pp. 767–8.

- ^ a b V. Bogdanov, C. Woodstra and S. T. Erlewine, All Music Guide to Rock: the Definitive Guide to Rock, Pop, and Soul (Milwaukee, WI: Backbeat Books, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 0-87930-653-X, pp. 494–5.

- ^ a b c d S. T. Erlewine, "Bon Jovi", Allmusic, retrieved 20 June 2010.

- ^ "The Billboard 200". Billboard. Nielsen Business concern Media, Inc. 1988-06-25. Retrieved 2010-03-05 .

- ^ "The Billboard 200". Billboard. Nielsen Business concern Media, Inc. 1988-07-23. Retrieved 2010-03-05 .

- ^ "The Billboard 200". Billboard. Nielsen Business organization Media, Inc. 1988-08-06. Retrieved 2010-03-05 .

- ^ "The Billboard 200". Billboard. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. 1988-10-15. Retrieved 2010-03-05 .

- ^ S. T. Erlewine, "Extreme", Allmusic, retrieved 10 February 2011.

- ^ S. T. Erlewine, "Warrant", Allmusic, retrieved ten February 2011.

- ^ Southward. Huey, "Slaughter", Allmusic, retrieved x Feb 2011.

- ^ South. T. Erlewine, "Firehouse", Allmusic, retrieved 10 February 2011.

- ^ Five. Bogdanov, C. Woodstra and S. T. Erlewine, All Music Guide to Stone: the Definitive Guide to Rock, Popular, and Soul (Milwaukee, WI: Backbeat Books, third edn., 2002), ISBN 0-87930-653-X, pp. 1018–9.

- ^ "RIAA Gold & Platinum database". Recording Industry Association of America . Retrieved 16 Feb 2009.

- ^ South. T. Erlewine, "The Blackness Crowes Shake Your Money Maker", Allmusic, retrieved xiii February 2011.

- ^ "RIAA Certifications". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved 16 January 2010.

- ^ "Def Leppard – the Band" BBC h2g2, retrieved xviii June 2010.

- ^ a b "Grunge", Allmusic, retrieved 18 June 2010.

- ^ a b "Hair metallic", Allmusic, retrieved 14 June 2010.

- ^ a b V. Bogdanov, C. Woodstra and South. T. Erlewine, All Music Guide to Rock: the Definitive Guide to Rock, Popular, and Soul (Backbeat Books, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 0-87930-653-X, pp. 1344–vii.

- ^ S. T. Erlewine, "Pearl Jam", Allmusic, retrieved 23 June 2010.

- ^ A. Budofsky, The Drummer: 100 Years of Rhythmic Power and Invention (Milwaukee, WI: Hal Leonard Corporation, 2006), ISBN 1-4234-0567-6, p. 148.

- ^ S. T. Erlewine, "Stone Temple Pilots", Allmusic, retrieved 20 June 2010.

- ^ a b Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Manic Street Preachers - Biography & History". AllMusic . Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ^ Due south. T. Erlewine and Thou. Prato, "Guns N' Roses", Allmusic, retrieved xix June 2010.

- ^ a b c Southward. T. Erlewine, "AC/DC", Allmusic, retrieved 20 July 2010.

- ^ "the biography of Bon Jovi – singer life story". Retrieved 2013-04-eighteen .

- ^ "Bon Jovi Songs (Top Songs / Nautical chart Singles Discography)". Retrieved 2013-04-18 .

- ^ V. Bogdanov, C. Woodstra and S. T. Erlewine, All Music Guide to Rock: the Definitive Guide to Rock, Pop, and Soul (Milwaukee, WI: Backbeat Books, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 0-87930-653-Ten, pp. 729–30.

- ^ a b "Mail-grunge", Allmusic, retrieved 17 Jan 2010.

- ^ J. Ankeny, "Feeder", Allmusic, retrieved xx June 2010.

- ^ J. Damas, "Stereophonics: Functioning and Cocktails", Allmusic, retrieved twenty June 2010.

- ^ "Heart Discography and Chart Positions". allmusic.com.

- ^ S. T. Erlewine and K. Prato, "Van Halen", Allmusic, retrieved 20 June 2010.

- ^ B. Eder and South. T. Erlewine, "The Who", Allmusic, retrieved twenty June 2010.

- ^ W. Ruhlmann, "Black Sabbath", Allmusic, retrieved 20 June 2010.

- ^ H. MacBain, "Led Zeppelin reunion: the review" New Musical Express, 10 December 2007, retrieved twenty June 2010.

- ^ 1000. Wilson, "Audioslave", Allmusic, retrieved twenty June 2010.

- ^ J. Loftus, "Velvet Revolver", Allmusic, retrieved 20 June 2010.

- ^ "Gold and Platinum Database Search". Recording Manufacture Association of America. Archived from the original on 2015-09-08. Retrieved 2009-11-25 .

- ^ E. Rivadavia, "The Sword: 'Historic period of Winters'", Allmusic, retrieved 11 June 2007.

- ^ E. Rivadavia, "'Wolfmother: 'Cosmic Egg'", Allmusic, retrieved 11 June 2007.

- ^ J. Macgregor, "Airbourne", Allmusic, retrieved 19 June 2010.

- ^ H. Phares, The Darkness, Allmusic, retrieved 11 June 2007.

- ^ "Nautical chart Stats: The Darkness", Chart Stats, retrieved 17 June 2008.

- ^ J. Lymangrover, "Steel Panther", Allmusic, retrieved 19 June 2010.

- ^ M. Brown, "Vains of Jenna", Allmusic, retrieved 19 June 2010.

- ^ S. Huey, "Hardcore Superstar", Allmusic, retrieved 19 June 2010.

- ^ K. R. Hoffman, "Crashdïet", Allmusic, retrieved xix June 2010.

- ^ T. Grierson, "Mail service-Grunge: A History of Post-Grunge Rock", Almost.com, retrieved 1 January 2010.

- ^ H. Phares, "Andrew W.K.", Allmusic, retrieved 19 June 2010.

- ^ J. Loftus, "Beautiful Creatures", Allmusic, retrieved 20 June 2010.

- ^ J. Loftus, "Buckcherry", Allmusic, retrieved 19 June 2010.

- ^ S. J. Blackman, Chilling out: the Cultural Politics of Substance Consumption, Youth and Drug Policy (McGraw-Hill International, 2004), ISBN 0-335-20072-9, p. 90.

- ^ J. Ankeny and G. Prato, "Queens of the Stone Age", Allmusic, retrieved nineteen June 2010.

- ^ M. Sutton, "Three Days Grace", Allmusic, retrieved 19 June 2010.

- ^ P. Smitz, C. Bain, S. Bao, S. Farfor, Commonwealth of australia (Footscray Victoria: Lonely Planet, 14th edn., 2005), ISBN ane-74059-740-0, p. 58.

- ^ C. Rawlings-Way, Solitary Planet New Zealand (Footscray Victoria: Lonely Planet, 14th edn., 2008), ISBN i-74104-816-8, p. 52.

- ^ H. Phares, "Them Crooked Vultures", Allmusic, retrieved 2 Oct 2010.

- ^ "Them Kleptomaniacal Vultures – Them Crooked Vultures", Acharts.us, retrieved two October 2010.

Further reading [edit]

- Nicolas Bénard, La civilization Hard Rock, Paris, Dilecta, 2008.

- Nicolas Bénard, Métalorama, ethnologie d'une civilization contemporaine, 1983–2010, Rosières-en-Haye, Camion Blanc, 2011.

- Fast, Susan (2001). In the Houses of the Holy: Led Zeppelin and the Power of Rock Music. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-511756-five

- Fast, Susan (2005). "Led Zeppelin and the Construction of Masculinity," in Music Cultures in the United States, ed. Ellen Koskoff. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-96588-8

- Guibert, Gérôme, and Fabien Hein (ed.) (2007), "Les Scènes Metal. Sciences sociales et pratiques culturelles radicales", Volume! La revue des musiques populaires, n°5-2, Bordeaux: Éditions Mélanie Seteun. ISBN 978-2-913169-24-one

- Kahn-Harris, Keith, Extreme Metal: Music and Culture on the Edge, Oxford: Berg, 2007, ISBN 1-84520-399-2

- Kahn-Harris, Keith and Fabien Hein (2007), "Metal studies: a bibliography", Volume! La revue des musiques populaires, n°5-2, Bordeaux: Éditions Mélanie Seteun. ISBN 978-2-913169-24-1 Downloadable here

- Weinstein, Deena (1991). Heavy Metal: A Cultural Folklore. Lexington. ISBN 0-669-21837-v. Revised edition: (2000). Heavy Metal: The Music and its Culture. Da Capo. ISBN 0-306-80970-2.

External links [edit]

-

Media related to hard rock at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to hard rock at Wikimedia Commons

0 Response to "Fashion of the 70s Lynyrd Skynyrd Album Covers"

Post a Comment